Fox squirrel

| Fox squirrel[1] Temporal range:

Middle Holocene–present (7,000–0 YBP)[2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fox squirrel in J. Clark Salyer National Wildlife Refuge, North Dakota | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Sciuridae |

| Genus: | Sciurus |

| Subgenus: | Sciurus |

| Species: | S. niger

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sciurus niger | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

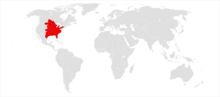

| Fox squirrel's range (excludes introduced populations) | |

The fox squirrel (Sciurus niger), also known as the eastern fox squirrel or Bryant's fox squirrel,[3] is the largest species of tree squirrel native to North America. Despite the differences in size and coloration, it is sometimes mistaken for American red squirrels or eastern gray squirrels in areas where the species co-exist.[5]

Description

[edit]The fox squirrel's total length measures 20 to 30 in (50.8 to 76.2 cm), with a body length of 10 to 15 in (25.4 to 38.1 cm) and a similar tail length. They range in weight from 1.0 to 2.5 lb (453.6 to 1,134.0 g).[6] There is no sexual dimorphism in size or appearance. Individuals tend to be smaller in the West. There are three distinct geographical morphs in coloration. In most areas, the animal's upper body is brown-grey to brown-yellow with a typically brownish-orange underside, while in eastern regions, such as the Appalachians, there are more strikingly-patterned dark brown and black squirrels with white bands on the face and tail. In the South and parts of Nebraska and Iowa along the Missouri River,[7] there are populations with uniform black coats.

To help with climbing, the squirrels have sharp claws, developed extensors of digits and flexors of forearms, and abdominal musculature.[8] Fox squirrels have excellent vision and well-developed senses of hearing and smell. They use scent-marking to communicate with other fox squirrels.[8] "Fox squirrels also have several sets of vibrissae, hairs or whiskers that are used as touch receptors to sense the environment. These are found above and below their eyes, on their chin and nose, and on each forearm."[8] The dental formula of S. niger is 1.0.1.31.0.1.3 × 2 = 20.[9]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The fox squirrel's natural range extends through most of the eastern United States, north into the southern prairie provinces of Canada, and west to the Dakotas, Colorado, and Texas. They are absent (except for vagrants) in New England, New Jersey, most of New York, northern and eastern Pennsylvania, Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces of Canada. They have been introduced to both northern and southern California,[10] Oregon,[11] Idaho,[12] Montana,[12] Washington,[12] and New Mexico,[12] as well as Ontario and British Columbia in Canada. While very versatile in their habitat choices, fox squirrels are most often found in forest patches of 40 hectares or less with an open understory, or in urban neighborhoods with trees. They thrive best among oak, hickory, walnut, pecan and pine trees, storing their nuts for winter. Western range extensions in Great Plains regions such as Kansas are associated with riverine corridors of cottonwood. Some subspecies native to several eastern U.S. states are the Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel (S. n. cinereus),[6] and the southern fox squirrel (S. n. niger).[13]

Fox squirrels are most abundant in open forest stands with little understory vegetation; they are not found in stands with dense undergrowth. Ideal habitat is small stands of large trees interspersed with agricultural land.[14] The size and spacing of pines and oaks are among the important features of fox squirrel habitat. The actual species of pines and oaks themselves may not always be a major consideration in defining fox squirrel habitat.[6] Fox squirrels are often observed foraging on the ground several hundred meters from the nearest woodlot. Fox squirrels also commonly occupy forest edge habitat.[15]

Fox squirrels have two types of shelters: leaf nests (dreys) and tree dens. They may have two tree cavity homes or a tree cavity and a leaf nest. Tree dens are preferred over leaf nests during the winter and for raising young. When den trees are scarce, leaf nests are used year-round.[16][17] Leaf nests are built during the summer months in forks of deciduous trees about 30 feet (9 m) above the ground. Fox squirrels use natural cavities and crotches (forked branches of a tree) as tree dens.[16] Den trees in Ohio had an average diameter at breast height (d.b.h.) of 21 inches (53 cm) and were an average of 58.6 yards (53.6 m) from the nearest woodland border. About 88% of den trees in eastern Texas had an average d.b.h. (diameter at breast height) of 12 inches (30 cm) or more.[14] Dens are usually 6 inches (15 cm) wide and 14–16 inches (36–41 cm) inches deep. Den openings are generally circular and about 2.9 to 3.7 inches (7.4 to 9.4 cm). Fox squirrels may make their own den in a hollow tree by cutting through the interior; however, they generally use natural cavities or cavities created by northern flickers (Colaptes auratus) or red-headed woodpeckers (Melanerpes erythrocephalus). Crow nests have also been used by fox squirrels.[17]

Fox squirrels use leaf nests or tree cavities for shelter and litter rearing.[14] Forest stands dominated by mature to over-mature trees provide cavities and a sufficient number of sites for leaf nests to meet the cover requirements. Overstory trees with an average d.b.h. of 15 inches (38 cm) or more generally provide adequate cover and reproductive habitat. Optimum tree canopy closure for fox squirrels is from 20% to 60%. Optimum conditions of understory closure occur when the shrub-crown closure is 30% or less.[14]

Fox squirrels are tolerant of human proximity, and even thrive in crowded urban and suburban environments. They exploit human habitations for sources of food and nesting sites, being as happy nesting in an attic as they are in a hollow tree.[18]

As an invasive species

[edit]In Europe, Sciurus niger has been included since 2016 in the list of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern (the Union list).[19] This implies that this species cannot be imported, bred, transported, commercialized, or intentionally released into the environment in the whole of the European Union.[20]

Behavior and ecology

[edit]

Fox squirrels are strictly diurnal, non-territorial, and spend more of their time on the ground than most other tree squirrels. They are still, however, agile climbers. They construct two types of homes called "dreys", depending on the season. Summer dreys are often little more than platforms of sticks high in the branches of trees, while winter dens are usually hollowed out of tree trunks by a succession of occupants over as many as 30 years. Cohabitation of these dens is not uncommon, particularly among breeding pairs.

Fox squirrels will form caches by burying food items for later consumption.[9] They like to store foods that are shelled and high in fat, such as acorns and nuts. Shelled foods are favored because they are less likely to spoil than non-shelled foods, and fatty foods are valued for their high energy density.[21][22]

Fox squirrels are not particularly gregarious or playful; in fact, they have been described as solitary and asocial creatures, coming together only in breeding season.[23] They have a large vocabulary, consisting most notably of an assortment of clucking and chucking sounds, not unlike some "game" birds, and they warn of approaching threats with distress screams. In the spring and autumn, groups of fox squirrels clucking and chucking together can make a small ruckus. They also make high-pitched whines during mating. When threatening another fox squirrel, they will stand upright with their tail over their back and flick it.[8] Fox squirrels are impressive jumpers, easily spanning 15 feet in horizontal leaps and free-falling 20 feet or more to a soft landing on a tree limb or tree trunk.

Diet

[edit]Food habits of fox squirrels depend largely on geographic location.[24] In general, fox squirrel foods include mast, tree buds, insects, tubers, bulbs, roots, bird eggs, pine nuts and spring-fruiting trees, and fungi. Agricultural crops such as corn, soybeans, oats, wheat, and fruit are also eaten.[6][14][17][24] Mast eaten by fox squirrels commonly includes turkey oak (Quercus laevis), southern red oak (Quercus falcata), blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica), bluejack oak (Quercus incana), post oak (Quercus stellata), and live oak (Quercus virginiana).[6]

In Illinois, fox squirrels rely heavily on hickories from late August through September. Pecans, black walnuts (Juglans nigra), osage orange (Maclura pomifera) fruits, and corn are also important fall foods. In early spring, elm buds and seeds are the most important food. In May and June, mulberries (Morus spp.) are heavily used. By early summer, corn in the milk stage becomes a primary food.[24]

During the winter in Kansas, osage orange is a staple item supplemented with seeds of the Kentucky coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioicus) and honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), corn, wheat, eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides var. deltoides) bark, ash seeds, and eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) berries. In the spring, fox squirrels feed primarily on buds of elm, maple, and oaks but also on newly sprouting leaves and insect larvae.[24]

Fox squirrels in Ohio prefer hickory nuts, acorns, corn, and black walnuts. The squirrels are absent where two or more of these mast trees are missing. Fox squirrels also eat buckeyes, seeds and buds of maple and elm, hazelnuts (Corylus spp.), blackberries (Rubus spp.), and tree bark. In March, they feed mainly on buds and seeds of elm, maple, and willow. In Ohio, eastern fox squirrels have the following order of food preference: white oak (Quercus alba) acorns, black oak (Quercus velutina) acorns, red oak (Quercus rubra) acorns, walnuts, and corn.[24]

In eastern Texas, fox squirrels prefer the acorns of bluejack oak, pecans, southern red oak (Q. falcata), and overcup oak (Q. lyrata). The least preferred foods are acorns of swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii) and overcup oak. In California, fox squirrels feed on English walnuts (J. regia), oranges, avocados, strawberries, and tomatoes. In midwinter, they feed on eucalyptus seeds.[24]

In Michigan, fox squirrels feed on a variety of foods throughout the year. Spring foods are mainly tree buds and flowers, insects, bird eggs, and seeds of red maple (Acer rubrum), silver maple (Acer saccharinum), and elms. Summer foods include a variety of berries, plum and cherry pits, fruits of basswood (Tilia americana), fruits of box elder (Acer negundo), black oak acorns, hickory nuts, seeds of sugar (Acer saccharum) and black maple (Acer nigrum), grains, insects, and unripe corn. Autumn foods consist mainly of acorns, hickory nuts, beechnuts, walnuts, butternuts (Juglans cinerea), and hazelnuts. Caches of acorns and hickory nuts are heavily used in winter.[24]

Reproduction

[edit]

Female fox squirrels come into estrus in mid-December or early January, then again in June. They normally produce two litters a year; however, yearling females may only produce one.[24] Females become sexually mature at 10 to 11 months of age and usually produce their first litter when they are 1 year old.[24]

Gestation occurs over a period of 44 to 45 days. The earliest litters appear in late January; most births occur in mid-March and July. The average litter size is three, but can vary according to season and food conditions.[24]

Tree cavities, usually those formed by woodpeckers, are remodeled into winter dens and often serve as nurseries for late winter litters. If existing trees lack cavities, leaf nests known as dreys are built by cutting twigs with leaves and weaving them into warm, waterproof shelters. Similar leafy platforms are built for summer litters and are often called "cooling beds."[25]

Fox squirrels, like other tree squirrels, develop slowly compared to others. At birth, the young are blind, without fur, and helpless. Their eyes open at 4 to 5 weeks and their ears open at 6 weeks. Fox squirrels are weaned between 12 and 14 weeks, but may not be self-supporting until 16 weeks.[17][24] Juveniles usually disperse in September or October, but may den either together or with their mother during their first winter.[16]

Mortality

[edit]In captivity, fox squirrels have been known to live about 18 years, but in the wild, most fox squirrels die before they become adults.[8] Their maximum life expectancy is typically 12.6 years for females and 8.6 years for males. Because of overhunting and the destruction of mature forests, many subspecies of fox squirrel are endangered.[8] Another major cause of fox squirrel population decline is mange mites (Cnemidoptes spp.) along with severe winter weather.[24]

Relatively few natural predators can regularly capture adult fox squirrels. Of these predators, most only take fox squirrels opportunistically.[6] Predators include bobcats (Lynx rufus), Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), red-shouldered hawks (Buteo lineatus), great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), barred owls (Strix varia), and coyotes (Canis latrans). Former predators extirpated from most of the fox squirrel's range include cougars (Puma concolor) and wolves (Canis lupus).[6][16][24] Nestlings and young fox squirrels are particularly vulnerable to climbing predators such as raccoons (Procyon lotor), opossums (Didelphis virginiana), rat snakes (Pantherophis spp.), and pine snakes (Pituophis melanoleucus). In those states where fox squirrels are not protected, they are considered a game animal.[6] Fox squirrels were an important source of meat for European settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries. They are still hunted over most of their range.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit] This article incorporates public domain material from Sciurus niger. United States Department of Agriculture.

This article incorporates public domain material from Sciurus niger. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ Thorington, R.W. Jr.; Hoffmann, R.S. (2005). "Sciurus (Sciurus) niger". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference (3rd ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 754–818. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 26158608.

- ^ Dooley Jr., Alton C.; Moncrief, Nancy D. (March 2012). "Fluorescence provides evidence of congenital erythropoietic porphyria in 7000-year-old specimens of the eastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) from the Devil's Den". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (2): 495–497. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..495D. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.639422. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b Linzey, A.V.; Timm, R.; Emmons, L.; Reid, F. (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Sciurus niger". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T20016A115155257. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T20016A22247226.en. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Sciurus niger". NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Graham, Donna. "Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger)". Northern State University. South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks. Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Van Gelden, Richard George. (1982). Mammals of the National Parks. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press

- ^ Wilson, James A. (2013). "Westward Expansion of Melanistic Fox Squirrels (Sciurus niger) in Omaha, Nebraska". American Midland Naturalist. 170 (2): 393–401. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-170.2.393. ISSN 0003-0031. JSTOR 23525591. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sciurus niger page". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ^ a b Koprowski, John L. (1994-12-02). "Sciurus niger". Mammalian Species (479): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504263. ISSN 0076-3519. JSTOR 3504263..

- ^ "Southern California Fox Squirrel Page". www.calstatela.edu. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ^ "Mammal Species of Oregon – Squirrels". Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ a b c d "TREE SQUIRRELS AS INVASIVE SPECIES: CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS" (PDF). www.ag.arizona.edu. Retrieved 2014-10-08.

- ^ "SCDNR - Mammal - Species - Southern Fox Squirrel". www.dnr.sc.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-03.

- ^ a b c d e Allen, A. W. 1982. Habitat suitability index models: fox squirrel. FWS/OBS-82/10.18. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service

- ^ Dueser, Raymond D.; Dooley, James L., Jr.; Taylor, Gary J. (1988). Habitat structure, forest composition and landscape dimensions as components of habitat suitability for the Delmarva fox squirrel. In: Management of amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals in North America: Proceedings of the symposium; 1988 July 19–21; Flagstaff, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-166. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 414–421

- ^ a b c d Banfield, A. W. F. (1974). The mammals of Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ a b c d MacClintock, Dorcas. (1970). Squirrels of North America. New York: Litton Educational Publishing, Inc.

- ^ "Wild Care: Meet the Fox Squirrels".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "List of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern - Environment - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ^ "REGULATION (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European parliament and of the council of 22 October 2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species".

- ^ Preston, Stephanie D.; Jacobs, Lucia F. (2009). "Mechanisms of Cache Decision Making in Fox Squirrels (Sciurus niger)". Journal of Mammalogy. 90 (4): 787–795. doi:10.1644/08-mamm-a-254.1. JSTOR 27755064.

- ^ Kotler, Burt P.; Brown, Joel S.; Hickey, Michael (1999). "Food Storability and the Foraging Behavior of Fox Squirrels (Sciurus niger)". The American Midland Naturalist. 142 (1): 77–86. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(1999)142[0077:fsatfb]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 2426894. S2CID 86732602.

- ^ Carraway, Mike. "Fox Squirrel, North Carolina Wildlife Profiles" (PDF). The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. n.p. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Chapman, Joseph A.; Feldhamer, George A., eds. 1982. Wild mammals of North America. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press

- ^ "DNR: Fox Squirrel". www.in.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

External links

[edit]- "Sciurus niger". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2006-03-26.

- Enature treatment: Eastern Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger)

- American Society of Mammalogists: Mammalian species account of Sciurus niger

- Smithsonian: Eastern Fox Squirrel article

- Digimorph: 3D visualization of a Fox Squirrel skull

- The Squirrel Project—UIC study of territorial interleavings of Grey and Fox Squirrels, in urban Chicago

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- NatureServe secure species

- Sciurus niger

- Rodents of Canada

- Rodents of the United States

- Fauna of the Eastern United States

- Fauna of the Plains-Midwest (United States)

- Mammals described in 1758

- Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

- Least concern biota of North America

- Least concern biota of the United States